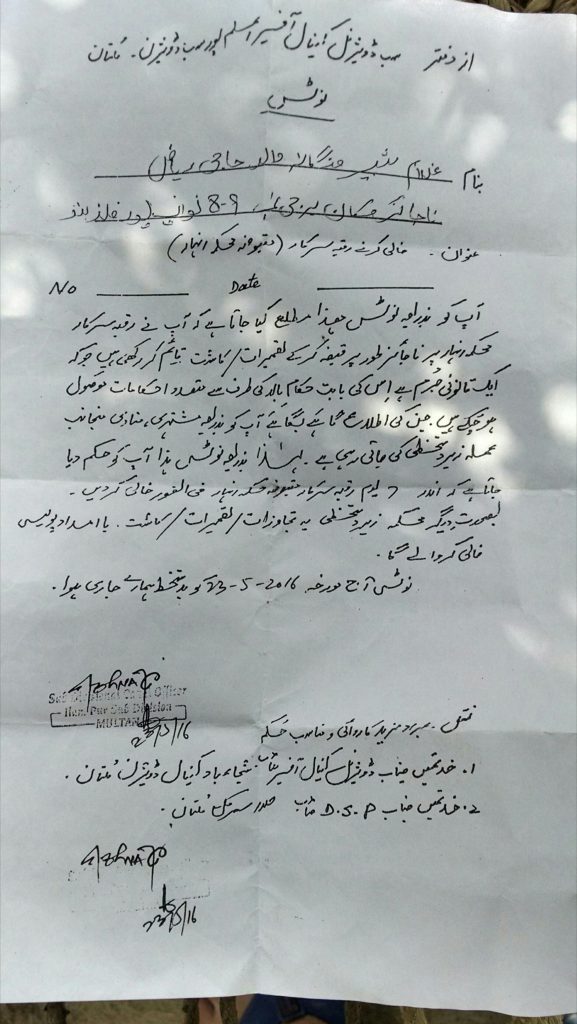

The village of Kanwan Wali, a government sponsored tent community on an embankment vulnerable to flooding. | Photography: Kasim Tirmizey

Kachchhi – sone di pachchhi.

Riverine land is a basket of gold.

– Punjabi proverb in the Shahpur District of Punjab

Under a burning sun, the Khana Padosh tribe of the Moza Vehlan village in Multan tehsil make do with tattered and colorful patches of cloth and wooden sticks to construct their tents. After massive flooding inundated their village, constructed on katchi (riverine) lands, they have been forced to temporarily reside on a nearby band (embankment).

While the katchi lands are prone to flooding, the Khana Padosh say they have little choice but to live there. They would hardly describe the land they live on as a “basket of gold” as the old Punjabi proverb goes. The katchi was considered bountiful in the 19th century, when farming in western Punjab was done through inundated agriculture. It was a system that thrived on regular floodwaters making riverine lands fertile for agriculture. At that time, farmers would organize agrarian life according to the rhythms of floods. Other communities, such as the Khana Padosh, in this part of Punjab were nomadic pastoralists.

Western Punjab underwent massive transformation under British rule through the introduction of canal irrigation. This signalled the demise of inundated agriculture and nomadic pastoralism. The British were interested in increasing the agrarian frontier in order to provide cheap food in England and to gain greater land revenue through rent. In the new political economy, katchi lands were marginal and vulnerable territory.

The Khana Padosh living on the embankment.

The Khana Padosh were historically a nomadic tribe that tended to livestock. The introduction of canal colonies interrupted that mode of life, however. The British considered many nomadic communities to be ‘criminal tribes’. That term, ‘criminal’, had less to do with the law, and more with the British government’s attempt to criminalize the entire nomadic pastoral way of life, seeing as it stood in opposition to their canal systems. The British demand to assimilate to a settler-farmer mode of life was, however, unconceivable for many nomadic tribes.

Today’s Khana Padosh tribe, like their forefathers, are technically landless. A local landowner has allowed the tribe to squat on a portion of the katchi land that he owns near the Chenab River for the sole purposes of temporary settlement.

Bashir Ahmed, of the Kanwan Wali village, is living temporarily on an embankment in a government sponsored tent community in Multan tehsil. Unlike the Khana Padosh, he and his fellow villagers work as sharecroppers on katchi land for a landowner. He explains why he and others live on the katchi: “Us, the poor, we don’t have any money or assets that [allow us to] live in the pakka [settled] areas. That is why we live in the center of the river. That is why we live in the katchi. We have to produce what we can so we can eat.”

Others from Bashir’s village commented that they live on the katchi because land there is cheaper to lease.

Azra Talat Sayeed, the director of the NGO Roots for Equity, which focuses on the political mobilization of peasant and labour communities, argues that the fundamental issue behind the impact of the floods is landlessness:

“Many thousands of these people live on the banks of various [rivers] which run the length and breadth of the country, only because Pakistan has failed to implement even the most rudimentary of land reforms, let alone a policy that would allow for a just equitable distribution of land. Feudal lords, who are fast changing into ‘corporate land lords,’ rule the country and millions of farmers are forced to eke out a very meagre earning by working as sharecroppers, agricultural workers or contract farmers. Others are forced to endanger their lives and livelihood by living in what could be called a ‘seasonal red zone’; no doubt global warming and ensuing climate change have exacerbated the situation.”

Landless people and smallholders represent 92 percent of the population in present day Pakistan. For the rural poor, katchilands are the last resort for survival. While some nomadic tribes opted to settle in one area, have received small portions of land to practice agriculture on, the Khana Padosh tribe opted not to do so. The Khana Padosh do not have a history of agrarian life, nor do they engage in farming today. Farming has been a mode of life that requires an intense amount of apprenticeship and practice, and, most of all, access to land that is not vulnerable to severe inundation. The Khana Padosh say that they mostly continue to act as pastoralists, tending to livestock under contract with wealthy farmers. Others seek daily wages as labourers in the nearby city of Multan.

Communities across the katchi had a few days warning of the oncoming floods. These communities packed whatever houseware they could take with them, a few days worth of food, and headed towards the embankment.

Muhammad Ghulam with a basket that he made from wooden sticks to be sold in the market. This production continues in the embankment as means of livelihood.

“Our villages in the katchi have been totally inundated. Our homes have been destroyed,” Ghulam Muhammad of the Khana Padosh tribe told Tanqeed. “When we return to our village we will have to start from scratch. We don’t even have any food or tents. Things will worsen when the cold weather arrives and we are without proper shelter.”

While the government has been distributing basic rations and providing tents to some communities from the katchi, they have not given anything to the Khana Padosh.

“The government has not given us any rations. Nor do they allow us to sit in government sponsored tent communities,” says Muhammad.

Across Punjab, it is those villages that have connections with feudal lords or politicians that have generally been able to gain access to government rations. As the Khana Padosh are among the most marginalized of communities, they do not fit into the network of patronage. Bashir Ahmed says that they received government relief only after they repeatedly pressured officials into giving them their rights.

What are other possibilities for communities that live on the katchi in the face recurring floods? Roots for Equity has called for equitable redistribution of land as the only just way to address the issue. Without access to safe and fertile lands, millions will continue to reside on the vulnerable lands of the katchi. The Pakistan Kisan Mazdoor Tehreek (Pakistan Peasant Workers Party or PKMT) also advocates sustainable agriculture in the riverine lands. This is a medium-term measure to avoid the indebtedness that has resulted in the increasing entrenchment of corporate influence into agriculture in Pakistan.

In a field south of Multan tehsil, villagers who are members of the PKMT are experimenting with sustainable forms of agriculture. They are using a diversity of traditional, rather than corporate, seeds. They do not use pesticides and chemical fertilizers. PKMT realizes that the corporatization of agriculture is leading to the impoverishment of peasants. Opposing corporations and pro-corporate laws, such as the recent Punjab Seed Act of 2013, is necessary, but not enough. They also believe in creating their own alternative economies that are based on food sovereignty. Efforts are being made by some villages on the katchi in the Kanwan Wali village to transition to more self-reliant forms of agriculture.

But what do historical pastoralists like the Khana Padosh do when agriculture is not their calling? Equitable redistribution of land and ending a land-water ownership regime based on private property are important aspects within any long-term solution to the massive floods that have impacted the most marginalized of Pakistan in recent years. And no genuine land reforms will be possible without the mobilization of peasants, pastoralists, and labour.

Children of the village of Kanwan Wali on the embankment.

The socio-ecology of Punjab is shaped by the legacies of colonialism as well as ongoing feudalism, imperialism, and corporate agriculture. Colonialism introduced commercialized agriculture, whereby the landscape of western Punjab was transformed, moving away from inundated agriculture and nomadic pastoralism and towards irrigated agriculture. In this transforming landscape, nomadic pastoralists were increasingly marginalized and rendered criminal. In addition, those tribes and sub-castes that were loyal to the British, especially during the 1857 war of independence were given large landholdings. Marginal communities such as the Khana Padosh were made landless in a territory that was increasingly ruled by private property, where their nomadic way of life was being made extinct.

Millions of other landless people opt to lease cheap land or squat on the katchi. This is despite the fact that this is a zone of recurring flooding. Global warming has been attributed to the expansion of capitalism, most evident in the greenhouse gas emissions from industrialization. The wretched of the world, it seems, only experience the exploitation and oppression of capitalism, and now they are further forced to squat on the most vulnerable of lands. Ironically, in the case of the Punjab, it was these very lands that used to be considered “a basket of gold”, not so long ago.

Kasim Tirmizey is a doctoral candidate at the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University. He is currently based in Lahore, Pakistan.

http://www.tanqeed.org/2014/11/in-the-belly-of-the-river/