The recent floods sweeping through Pakistan have affected thousands of communities in Punjab and Azad Jammu and Kashmir. Thankfully, though the floods are not as devastating as of 2010, they have still created havoc in many communities costing nearly 300 lives to date.

Roots for Equity has been working in what is termed as ‘Kacha’ area in Multan, Punjab and Ghotki, Sindh with small and landless farmers since early this year. The context of this work is to work with rural communities learning and building systems of self-reliance in the face of climate crisis.

The kacha areas are basically lands that are situated along the river banks enclosed by embankments on both sides. The government has built the embankments to protect the populated rural and urban areas from flooding. In essence, communities should not inhabit the kacha area. But the reality of the landless is that they, in face of no access to land either for living or for agricultural production, many rural communities have no option but to live in these enclosed areas on the sides of the riverbanks. In the past few years, there has been decreasing quantity of water in the rivers and rural communities have actually even started living on the dried out riverbed.

Charpai (wooden frame bed) on the embankment

Transportation of personal items by boat to the embankments

The result is that during flooding, even of a very minor level, communities living in the kacha areas are displaced. Many of these communities loose their homes, daily living items, and in many instances the food stocks, especially wheat grains, nearly every year. With floods becoming a common feature, most people will evacuate children and their livestock early enough, but even then loss of homes and even food grains, and their very meager belongings is not possible.

Flooding in the katcha area

It needs to be highlighted that the real issue is of landlessness. Many thousands of these people live on the banks of various which run the length and breadth of the country, only because Pakistan has failed to implement even the most rudimentary of land reforms, let alone a policy that would allow for a just equitable distribution of land. Feudal lords, who are fast changing into ‘corporate land lords,’ rule the country and millions of farmers are forced to eke out a very meager earning by working as sharecroppers, agricultural workers or contract farmers. Others are forced to endanger their lives and livelihood by living in what could be called a ‘seasonal red zone’; no doubt global warming and ensuing climate change have exacerbated the situation.

The situation of the landless can be well depicted by the five communities in Multan that Roots with the help of Friends of Roots has been working with and helping to provide basic support and solidarity.

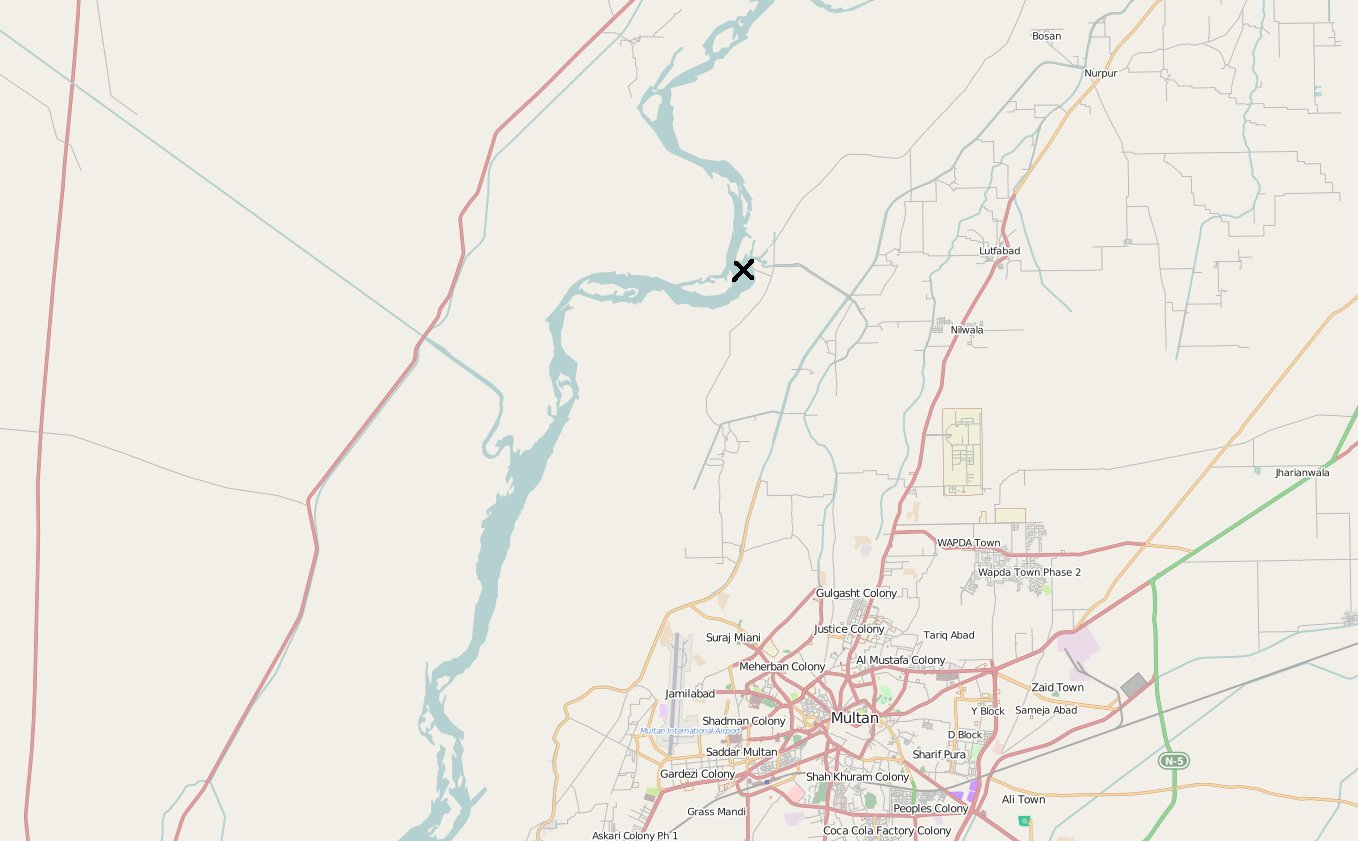

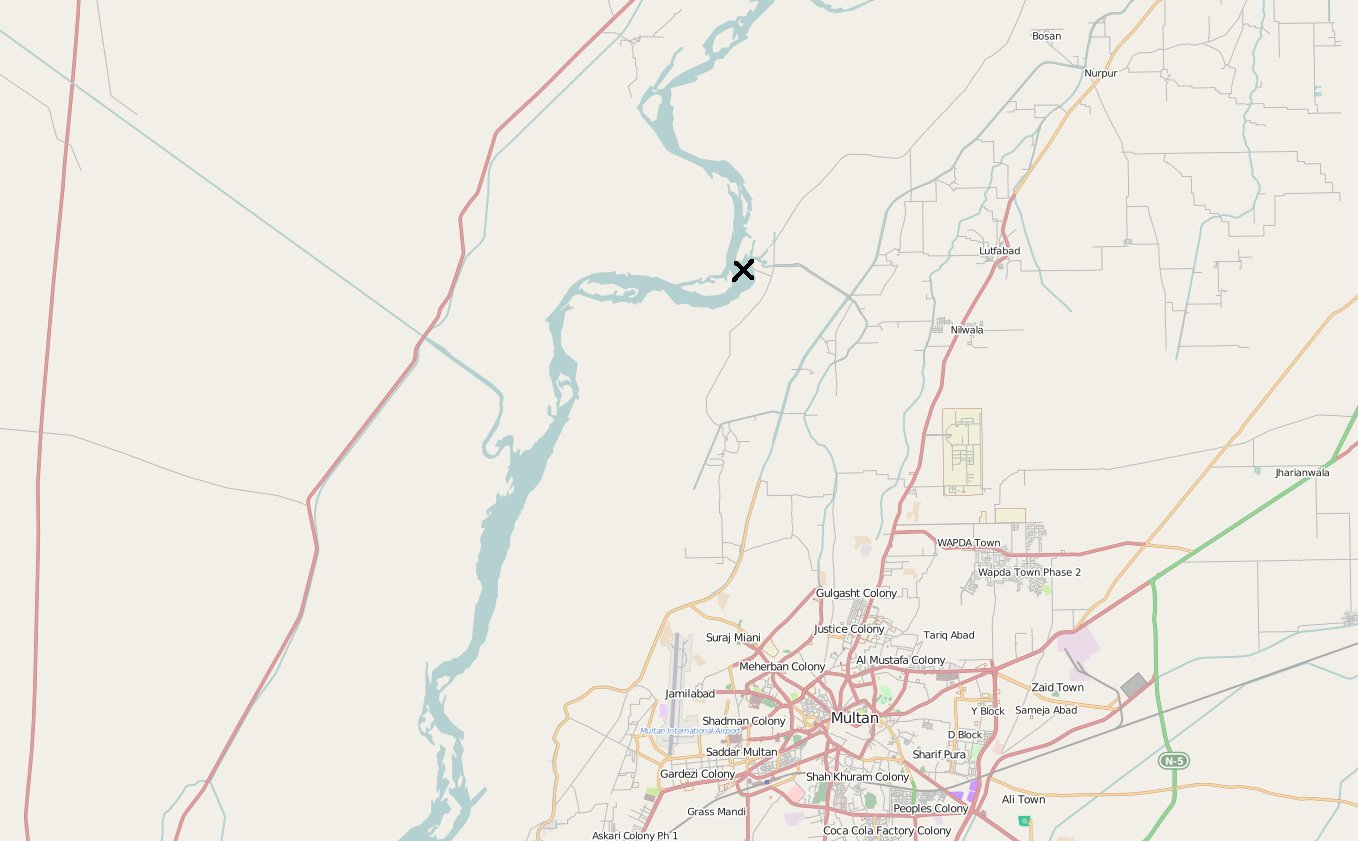

Map of Head Nawabpur, settlement of the khana badosh community during the floods, in the map, the embankment is considered part of the river:

View Larger Map

View Larger Map

In the past few years there has been an evolving pattern of floods occurring now mostly by the end of August or early September. However, this year, the general feeling in communities living in the kacha areas was that floods will not be severe and they would not really have to evacuate but just live with flooding of their lands. Due to consistent floods, year after year, many of the kacha area farmers have stopped planting crops during the flood season. This was the case nearly seen in all of the five communities. Only farmers in one village had sown rice; and here the entire harvest is now lost.

A mud house collapsed because of the flooding

The flooding proved to be of a high volume and water level rose was very high: in fact so high that authorities feared flooding of Multan city itself. Many strategic breaks in the embankments were made to avert water flow away from cities lying in the floodwater path.

Families from all five villages had to evacuate and are now living on various embankments or ‘bunds’ as they are called locally. Many families had tied their packed food grain on top of trees. Those who are going back to check on their homes report that much of it has been washed away. A woman had made a dozen razais (traditional comforters) for the coming winter. Another woman tells of her daughter’s trousseau that she had just completed. All of these are now lost.

Their mud homes have either collapsed totally or walls show cracks, making them no longer safe for living. Entire villages are still inundated with water. Where water has receded, the place is muddy infested with flies and mosquitoes. Some cannot even see the area where they were living as so water level is still high in these areas.

Of the five communities, three have been provided with tents by the government; the fourth community has been only partially settled with some families living on the embankment.

A tent community on the embankment (government provided tents)

Inside of a government issued tent

These in tent communities are receiving cooked food, enough for subsistence. It was observed that of the most well equipped tent communities is the one that has inhabitants who have direct affiliations with local feudal lords. The Federal Minister for the Ministry of National Food Security and Research is Mr Sikander Hyat Bosan is from Multan and has a huge constituency from the flooded areas in Multan. He is also one of the biggest feudal lords of Multan. A tent community organized by his political workers has housed nearly 50 families and they are well looked after, to the extent that they even have a supply of clean drinking water. The tent community has been placed on the base of the embankments, adjacent to mango orchards; hence are a bit further from the floodwaters. This means that the community has at least some shade and is not directly being affected by the blazing sun. But others, are not being given even shelter. There have been general observations that goods coming for flood relief are being stored in the dairas (traditional community space/room maintained by well off landlords for entertaining their male guests). Given the highly corrupt nature of governance maintained by Pakistani influential raise question marks on equitable distribution of these materials to the most needy.

The class-caste relationships are quite apparent as relief work is being carried out. A particular caste locally called pakhi bas, or khana badosh are considered nomads. People from this community face discrimination for instance, two separate villages from this particular caste have not been provided adequate shelter or food; local authorities have been heard saying that they are used to this way of life and being beggars they will only be helped if there are tents left-over. They have been pushed back to live on an embankment where neither official help is being provided nor civilian help is arriving as it is off the main embankments.

The khana badosh community who are receiving no government assistance

The khana badosh living on the embankment

The khana badosh living on the embankment

These people generally earn their living making wooden baskets, made from shrubs that the community members gather themselves. Some were able to bring their raw material with them and others not.

A woman weaves baskets from small branches as a source of income

Evacuation was carried out in small boats or in some cases on makeshift raft-like structures put on rubber tubes. People had placed their charpais (beds made from ropes woven around a wooden structure) upside down on rubber tubes. Some climb on to the charpais while others push it and wade through the water from their villages to the embankments. Hence, not all household items or other necessary material could be brought to the embankments. Men have been going to the city in search of work. But according to them, half the time they are unable to get any work, as there are so many laborers looking for daily wage labor. In addition, these people are far from the city and they pay for their travel from the embankment to the city, or try to walk at least partial distance. The minimum distance to the city area from where they are sitting on embankments is about eight kilometers away. Families with only a single adult male don’t feel comfortable leaving their families at the embankments.

A covered ceramic toiler made especially for the privacy needs of woman. This was constructed with funding from Friends of Roots.

These embankments have water on both sides making it immensely hot. On top of that, there are no trees and the blistering sun is making their existence even more miserable. Many of the households have no shelter. They have been sitting on the dirt with tilted charpais for forming a shade over them for protection against the sun.

These embankments have water on both sides making it immensely hot. On top of that, there are no trees and the blistering sun is making their existence even more miserable. Many of the households have no shelter. They have been sitting on the dirt with tilted charpais for forming a shade over them for protection against the sun.

Initially, water had to be fetched from some distance. But now all communities have hand pumps installed, making the chore somewhat more bearable.

Water hand pump installed through the funding of the Friends of Roots

However, things are much better in the government set-up tent campsites. In the two camps, medical teams have been placed. It is clear that people are not very satisfied with the services. Given, the class difference, and a highly class-conscious society, no doubt people are not being treated with respect and kindness.

Children are experiencing a variety of diseases in their new conditions, such as diarrhea, eye infections, itchiness, cold and fever. Medicines being dispensed may or may not be for the condition suffered.

It is criminal that government officials, especially those who are setting up tent communities, have been heard saying that the affected people in the kacha areas have not lost much because they generally did not grow crops in anticipation of the floods.

But as has been highlighted above, they have lost nearly everything. Their livestock are living without shelter; people have no access to fodder or they have to buy fodder for which they have no money. Many of them are falling sick due to first wading through water, and now living under a very hot sun, with flies and mosquitoes in plenty. There is poor hygiene, and close proximity of so many people in itself is a health hazard.

Livestock and animals in the tent community

Women are very uncomfortable as so many strangers are walking through the campsites at all times. There is absolutely no privacy, even when people are lying inside the tents (where it extremely hot and stuffy) they can be seen by the people outside. Cooking space is truly makeshift and they have no real water storage capacity and have to fetch water for every little thing from drinking water to cooking or cleaning.

Sanitation needs of women make it more difficult for them to look after themselves. Initially, there were no enclosed private spaces for daily ablutions. These have also been now looked after. But women lack basic material or sanitary napkins for maintaining hygiene. Before the installation of and washroom cubicles and hand pumps they were finding it even more difficult as washing soiled clothes and themselves was no easy task.

In nearly every community there are pregnant women. No doubt, for them, this time must be pure torture. Thankfully, at least in one campsite, it was observed that in tent community there were two separate tents for patients and they even had pedestal fans.

Community Practices of Self-Reliance

Disasters create havoc. There is an immediate need felt by the larger community to provide help and assistance to those who have been impacted. The focus on the needy and destitute is high. The suffering of the people is publicized; all this is needed especially to ensure that government provides to the needful immediately.

The dignity of people, their ability to look after themselves, and their courage also needs equal attention. Whereas often humanitarian agencies and the media treat those affected by the floods as victims, it is unfortunate that they rarely touch on how communities are looking after themselves in the wake of calamity. In the past two weeks since floodwaters have inundated Multan, the amazing forbearance of people, their courage and pride (khud-daree) has been seen again and again. In many spots across the flooded areas people are seen fishing hoping to not only find food for themselves but eke out some income if possible. According to a young man from Kanwa Walee village: “putting in a fishing net is really a luck of the draw. We may be able to earn Rs 4,000-5,000 [$US 40-50] in a day, or there may be no fish at all for 5-6 days.” Families those who have been able to save wood and bring it with them have already started making wooden baskets that they can sell. Some women have set up their mud stoves and are making snack items to be sold at the campsite or at nearby tea stalls. Women can also be observed making ropes from old cloth so that they can use the ropes make charpais. Their men folk have had the wooden frame made from local carpenters and ropes will be woven to make the bed within the frame.

Make-shift shelter using iron-frame beds to protect from the sun and heat

Travelling across the flood waters to villages with a bed on top of a wooden-frame bed

A woman makes a charpai in the camp

A woman makes a charpai in the camp

A make-shift covered toilet that was constructed by the community as a means to give woman privacy

Fishing nets that are being used as a means of catching fish for their subsistence

A man selling falooda (a sweet and cold drink made with vermicelli) from his cycle in the khana badosh community as a means of livelihood

Nearly all families have some form of livestock, from chickens to donkeys, cows, sheep and goats. Of course, a major concern and expense is fodder for these animals. Some of the communities are close to grasslands and are taking their animals their. Some families have collectively rented a small piece of land just to grow fodder. It is interesting that a family has actually put its livestock inside the tent and is living outside in the open. People are using their own livestock for milk and trying to supplement the small amount of foods being distributed by the government.

In general, it has been observed that even for transportation over the floodwaters to their homes, people have started ‘charpai’ ferries,’ meaning that as people want to go back to check on their homes, they make use of the charpais sitting on rubber tubes, go for a few hours and then come back to the campsite.

Going Back Home

Though the coming in floods catch the most media attention, and of course those moments create the worst havoc, the suffering and hardship of the affected communities actually continue for many months.

They cannot go home till at least end of October, depending on how quickly floodwaters recede and then the muddied area dries. They have now no warm bedding, nor any warm clothes, especially for children. And in another 6-8 weeks it will become very cold here in Multan.

By late October, early November, the wheat-sowing season will start. This is an immensely important crop not only for rural communities but also for the entire country’s food security. If land dries up by then for farmers with some agricultural land will need help with sowing wheat. For the landless, it will be a search for agricultural work, most probably they will have to go much further afield in the dry areas where there are no floods. Those who will be able to find the money will try to lease land. If there is dearth of land due to the floods, then even land lease will go up. There are also chances that some land would have been lost due to erosion.

So on one hand, livelihood pressures will be immense. At the same time, having lost not only most of their household goods but also their homes, there will be further hardship as they suffer the cold months without proper bedding or protective shelter. Cooking utensils are mostly lost, wood stocks for cooking food were lost and fresh stocks will have to be found which given the havoc will be no easy task. Animal fodder already scarce in winters will have to be searched.

In essence, the rural kacha area communities will start their lives once more. To what avail? In just a few months, maybe 10 months, if they are lucky another 24 months, the whole debacle will be faced again.

No doubt, the major problem is cause due to climate crisis. The fossil fuel driven paradigm of industrial production that has resulted in global warming, changed weather patterns, disrupting normal harvest seasons, melting glaciers rapidly in Pakistan are a major cause for floods year after year.

But as mentioned earlier, this is not the only cause for the suffering and destitution of these communities. If there was an equitable distribution of land, these people would not be forced to live on the river bed or on river embankments. They would not be made homeless every few months. They would not have to rely on others to provide for their shelter and food. Their dignity would not be so tattered! They would not be forced to almost begging for basic needs.

It is the right of the people to live in dignity and our government has the absolute responsibility to look after its people!