Roots for Equity has a sharp focus on women’s rights, especially economic rights of grass root women. A particular aspect is an inbuilt strong critique against patriarchy. Women’s Rights have been addressed In each of Roots for Equity’s thematic areas: food sovereignty, climate justice, and children’s education program and of course women empowerment.

Food Sovereignty Program

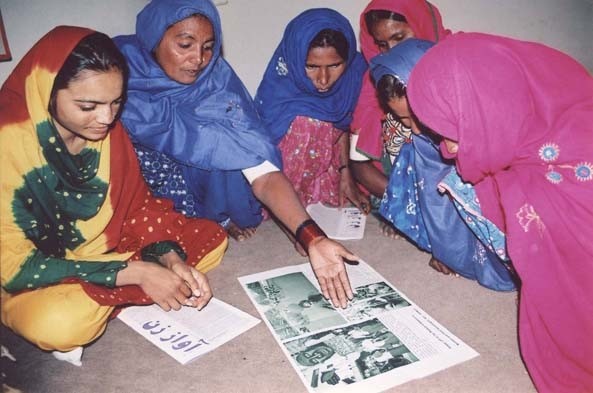

Roots for Equity initiated a rural women’s rights program in 2000 in rural Sindh. Later, with the greater understanding of Food Sovereignty as a political framework, it was adopted more holistically. Although the food sovereignty program was initiated with only landless women, over the years Roots changed its approach to include men and the entire village community. All our political education programs include analysis of exploitation and oppression at the hands of market forces, feudalism and patriarchy. With such topics under discussion at the village level the change in women’s attitude to life was dynamic. As part of the food sovereignty program, Roots initiated a small project where land was leased to women where they could grow food crops for their consumption. Understanding their rights, especially right to land had many women asking for their rights at home; this led to many repercussions. Men folk of these women were often mocked about these women’s increased mobility, and land being leased in their name. There were times when women from an entire village were not allowed to join our programs.

In order for women to sensitize their men folk, they started asking for political education programs to be held for their male family members as well. As women became more vocal there were many backlashes felt, especially from Muslim families. A number of women were categorically asked by their male family members that they could not leave the house.

After much discussion, it was agreed that the organization has to address the whole community and not only women. Therefore, since 2007 Roots has been organizing both male and female members of the households at the community level. This also has had repercussions. The female participation level has fallen. Patriarchal norms have been exerted even in Hindu and Christian communities where the pressure for women from their own community has been intense. According to these women there menfolk are saying, “if the Muslims don’t bring their women in the public why should we allow ‘our’ women to engage?”

However, the organization has continued to work on food sovereignty and women’s rights especially as farmers. Different strategies have been adopted to engage women advocating for women’s rights, farmer rights. Where it is possible joint programs are held for the whole community; otherwise segregated programs so that women may not be left out. But equal number of segregated programs for women is not possible. It is important to note that in society where women are not allowed out in the public spaces, it is also difficult to have women activists who would work at the village level so that there could greater number of events organized with women. The norm is that a very few women have ‘permission’ to leave the city to work in villages. Not only that working conditions are difficult in the rural areas, there is patriarchy in our homes as well and rarely women have the flexibility to stay overnight away from home. So patriarchy does not only have to be fought in the communities but also in our homes and our workspaces. This issue has been one of the strongest drawbacks that Roots has faced over the years in organizing rural women.

There is no doubt that the food sovereignty program has borne fruit. There are now many women from many districts, especially in Sindh who challenge feudalism, capitalism and patriarchy. For them the reality of capitalist markets is now evident:  the increased use of machines in land preparation, seed sowing and harvesting has decreased rural women’s access to work in agricultural production. At the same time, production costs are shooting higher and higher every year: the cost of chemical fertilizers, hybrid seeds and fuel are thrusting rural society into acute debt. With the task of feeding families a women’s burden in patriarchal societies, it is becoming very difficult for women to feed their families and they are constantly looking for more work to increase their earnings. These women not only work with their male members on their small land holdings (if they have any) but may also work assisting their husbands if they are sharecroppers and also as agricultural workers. So the physical toil is immense, all carried out with minimal nourishment at hand. Women form organized communities were willing to come out in public and raise their voices for their rights. They have been part of many mobilizations, some even willing to travel to other provinces as well go abroad for demonstrations against the World Trade Organization (WTO).

the increased use of machines in land preparation, seed sowing and harvesting has decreased rural women’s access to work in agricultural production. At the same time, production costs are shooting higher and higher every year: the cost of chemical fertilizers, hybrid seeds and fuel are thrusting rural society into acute debt. With the task of feeding families a women’s burden in patriarchal societies, it is becoming very difficult for women to feed their families and they are constantly looking for more work to increase their earnings. These women not only work with their male members on their small land holdings (if they have any) but may also work assisting their husbands if they are sharecroppers and also as agricultural workers. So the physical toil is immense, all carried out with minimal nourishment at hand. Women form organized communities were willing to come out in public and raise their voices for their rights. They have been part of many mobilizations, some even willing to travel to other provinces as well go abroad for demonstrations against the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Our work with peasants taught us that unless there was strong mass-based platform for small and landless farmers there could be no substantial change brought in the polarized class structure of society both in the urban and rural sectors. It is with this learning that we helped in the formation of a small and landless farmers alliance, namely the Pakistan Kissan Mazdoor Tehreek (PKMT).

PKMT’s constitution’s Article 2, Section 6 states, “it will ensure the active participation of women farmers and minorities in its membership.” This is a serious commitment and which PKMT is struggling to realize. Given the reality on ground, Roots for Equity has also started taking role in finding ways and means to develop women’s membership in PKMT. Given that more and more women are landless and work as agricultural women workers, Roots for Equity has started providing case studies and taken on fact finding to portray the acute economic hardship and hunger wages received by these women. For example, women may get as little as Rs 15-19 per day for vegetable picking. This is difficult onerous work mostly carried out in grueling heat. Wheat harvesting manually will be approximately earn them 12 kilograms of wheat which is equivalent to Rs 400 per day. For sugar cane harvest, they go with their men folk and are basically unpaid as men receive the money and don’t share with the women. Roots goal is to provide PKMT with the data that could be used by them to campaign for agricultural women workers. On one hand it will raise awareness on the terrible exploitation faced by women, on the other, women’s role in the PKMT structure will strenghen.

Women’s Economic Empowerment

The very first initiative that the organization had taken with respect to women empowerment had been its work with home-based women workers in a squatter settlement in Karachi, Sindh. The tentacles of Globalization have certainly reached the working class women, and especially the most exploited and oppressed sector of home-based women workers.

Structural Adjustment Programs in the 1990s had resulted in vast number of labor being unemployed or underemployed. There had been an immense increase in production prices and of course in the critical basic need items such as food, shelter and transport. The result was the immense increase in the number of home-based women workers; the patriarchal oppression of not allowing women mobility has resulted in extreme exploitation by market forces of these women who receive pittance as payment for hard, tedious labor. For instance, our initial house-to-house survey in a squatter settlement had yielded the information that women were putting together various parts of a ball point together – for 144 finished ball points they were paid Rs 2.50. At that time, USD 1 was approximately equal to Rs 45-50 (so the piece-rate they were receiving was not even equivalent to a pence). Similar atrocities were rampant. Roots decided to organize home-based women workers.

After two years of organizing, in 2000 we were able to form a Home-Based Women Workers Collective in Qasbah Colony and then spread the work in villages in two districts of Sindh, namely Tando Mohammad Khan and Badin. Our goal has been to ensure that women understand the roots of exploitation and oppression embedded in their lives through the joint pressure of feudalism, globalization and patriarchy.

The women’s collective on one hand provided women with decent work and on the other series of discussion sessions on the above three systems. Women’s paid and unpaid work was directly addressed; there was discussion on women’s immense contribution to the economic and social well being of their families and in society. It was of course not so easy: the Pakhtun women of Qasbah would not even come to the women’s center that Roots had opened directly in the community. Initially, our team used to take raw material needed for products (and what we called kits) directly to their home, one by one. After about 12 months we started saying that we could not come to their homes any more and they will have to come to the center, which was not more than 200-500 meter from their homes. It took a while; and then we closed the center and asked them to come to our office directly. The collective took care of the additional travelling expense, as that would have been a barrier. Now, all of them come directly to our office to collect kits and give us their finished products. Many of them now come alone, and others in groups.

As the collective matured and women gained confidence in the new relationship with the collective we organized exposure trips for them to the ‘posh’ urban markets; it allowed them to understand the worth of their products in Pakistani markets as well as abroad. It was important to make them realize how well received their products were and the very high prices at which they were being sold.

In the years from 1998 to date women associated with our collective have developed many of the products without any intervention from our side. Though in some products we have helped them to develop marketable items, by and large it is their own extremely beautiful ‘craftwomenship’ and marvelous skills that has allowed such vast expansion in the products that they produce. The products’ pictures have been placed under “Products of the Women’s Collective” in the main bar of the blog.

Roots was able to launch products by women at a stall at the Sunday Bazar in Defense Housing Society – such local daily bazars were the norm in the 1990s; the stall was initiated on May 7, 2000. In the early years the space for the daily bazaars were under municipal government administration; the collective stalls were hardly charged anything. Special projects pushed by urban women entrepreneurs and women activist even forced the government to provide free space for women-produced goods and handicrafts. Our collective was also able to benefit from such endeavors. In addition, Roots for Equity also started a small outlet called “Hunar-e-Zan” but was not able to maintain it because of the very high rental and salesperson salary; there were of course additional expenses of utility and administrative costs. This was leaching the savings that the collective was making. Since 2007, the collective has been totally self-financed by its own sales. Apart from the Sunday Bazaar stalls, the products produced by women were also sold at exhibitions and fairs in the city. Over the years, other shops in town were also buying the collective’s products.

As part of the collective, women were exposed to wholesale markets making them understand economies of scale. Women from these communities would manage the stall themselves and were able to engage with the market directly. Such direct contact allowed them to understand consumer tastes, administrative issues and most importantly, the value of their labor.

Today these women produce more than a hundred handmade products. However, with deregulation and privatization deeply rooted in our society, less and less daily bazars are operating; the district government outsourced the entire daily bazar administration, as well as the pieces of land allotted for holding the bazars. These daily bazars are now only left at very few points in the city. The spaces that were provided in the upper income areas are no more available. Currently, more than 250 women are associated with the collective administered by Roots – their products now are facing acute difficulties in being marketed. So, the failure of the government to provide marketing space for the most deserving – the small-scale women producers has in essence vanished!

Roots for Equity is struggling to market the goods produced by the home-based women workers from Qasbah Colony, Karachi as well as villages in rural Sindh. We hold sporadic exhibitions, or engage in exhibitions held by others. But the steady market that the collective enjoyed up until 2014 is now a thing of the past. The weakening of women’s economic freedom is indeed very evident from the way the government is exiting all responsibility for ensuring a dignified livelihood for the impoverished classes, especially women.

In 2010, Roots for Equity sponsored by UN Women had undertaken a countrywide study to quantify the number of home-based women workers in the country as well as to enumerate the types of goods that they are providing. The study also documented the social and economic conditions of these women. The study’s findings are that there are 12 million home-based women workers in Pakistan. The overwhelming cause of these women being forced to work at hunger wages at home were patriarchal forces which though had no shame in making women work but would not allow their work to be visible to society as this would be a huge ‘dishonor’ to the male members of the family. The research study is called “The Unacknowledged Treasures: the Home-based Women Labor of Pakistan.”

Children’s Education Program

In the early years of Roots, we had run numerous non-formal education centers in Qasbah and rural Sindh. As the non-formal education centre (NEC) was launched in Qasbah in June, 1998, it was decided to find philanthropic sponsorship for individual children who wanted to enter formal schooling. Our policy was to have equal number of boys and girls with a bias for girls both in the NECs as well as for the scholarship program. (For more details see the Children’s Education Program under ‘Our Work’ section).